Robert de La Salle and the French Claim of Louisiana, Part 2

Royal Tours New Orleans • January 18, 2018

Robert de La Salle and the French Claim of Louisiana, Part 2

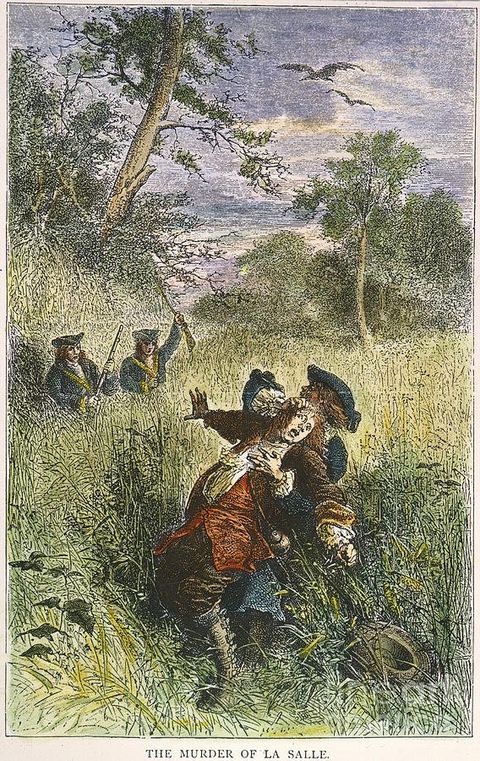

Mortally wounded, la Salle stayed alive long enough to be humiliated by his ‘friends’. He was stripped of all his clothing and jewelry and left to die where he fell, somewhere in present-day eastern Texas. He died one hour later. Yet, just five years prior, René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle, had the admiration of the French king and the world in his hands.

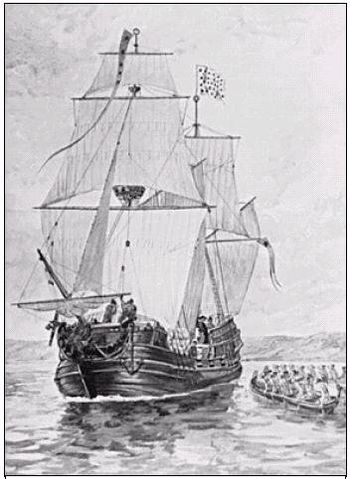

When la Salle returned to Canada from France in 1678 with the full support of King Louis XIV and a title of nobility, he began preparing for his exploration of the “western parts of New France” and his descent down the Mississippi River by exploring the Great Lakes and the Illinois Valley. Having been handed a valuable monopoly in the trade of buffalo hides, la Salle commissioned the building of the Griffon, the first commercial sailing vessel on Lake Erie, which he hoped would pay for an expedition into the interior as far as the Mississippi. Using the Griffon, la Salle intended to transport furs back to Montreal, but the seven-cannon, 45-ton ship sank with its six crew members and a load of furs before he could make a profit.

Following the sinking of the Griffon, la Salle canoed down the western bank of Lake Michigan while his friend, Henri de Tonti, crossed the lower Michigan peninsula on foot. They rejoined forces on the Illinois River about 70 miles southwest of present-day Chicago where they built Fort Crevecoeur (Fort Broken Heart). This fort led to the development of present-day Peoria, Illinois. Here, la Salle commissioned the building of another ship under the direction of Tonti, but while la Salle was gone for supplies, the men mutinied, destroyed the fort, and exiled Tonti.

After several additional setbacks, la Salle and Tonti, in February, 1682, finally launched their canoes into the icy waters of the Mississippi. In addition to Tonti, la Salle’s party consisted of more than forty Europeans and Native Americans. While navigating the Mississippi, la Salle stopped to construct Fort Prudhomme which later became the site of Memphis, Tennessee.

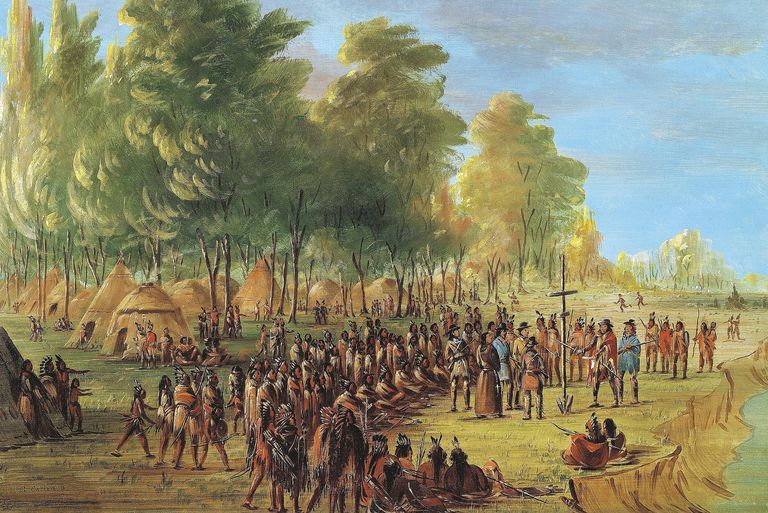

With the assistance of Arkansas Indian guides, La Salle’s group finally reached the point at which the Mississippi River flowed into the Gulf of Mexico (near present-day Venice, Louisiana) where he buried an engraved plate and planted a post with the inscription “Louis the Great, King of France and of Navarre, Reigns Here, April 9, 1682.” The king would not learn of La Salle’s discovery until a year later. On April 10, without taking the opportunity to explore the Gulf Coast and the Mississippi’s intricate web of tributaries, La Salle began the return voyage up the river. Once back in Illinois, la Salle and Tonti built Fort Saint Louis at Starved Rock in Illinois. La Salle left Tonti in charge while he returned to France to plan his next exploration.

To learn more about the fascinating history of New Orleans and the French Quarter, join Royal Tours

for a private walking tour of the French Quarter. Call us at 504-507-8333 or email us

to book!

King Louis XIV provided la Salle with a fleet of four vessels along with all the materials necessary to establish a colony, and la Salle again left his native country, but this time invested with high command and hoping perhaps to be the founder of an empire. But, as Gayarre recounts, la Salle’s fortunes began to turn. They left France on July 24, 1684, but La Salle soon found himself at odds with the officers and crew of the Joly, the ship on which la Salle sailed. La Salle refused to stop at Medeira, off the western coast of Africa, to resupply for the long trip across the Atlantic. The remaining distance across the Atlantic was undertaken in the heat of summer with very little water. To add to their difficulties, the Saint-Francois which was carrying food and supplies was captured by the Spanish. By the time they arrived at the French colony of St Domingue on Hispanola in the Caribbean, la Salle had lost more than 100 of his crew of 300 from desertion, disease, and death.

From Hispanola, la Salle set sail into the Gulf of Mexico with his three remaining ships in search of the mouth of the Mississippi River. But, whether due to navigation error, faulty maps, or the numerous false inlets which made finding the Mississippi River difficult, la Salle and his three ships sailed 500 miles west of their intended target to Matagorda Bay near present-day Houston, Texas. Convinced he was exactly where he wanted to be, la Salle sent the Belle and Amiable into what he was certain was the Mississippi River. While the Belle and Amiable were away, the Commander of the Joly, having reached the end of his contract, and set sail for France, leaving la Salle and his companions on shore.

When Belle and Amiable returned with their reports la Salle knew for certain that they were not on the Mississippi Delta. The two ships set out in search of the river, but the Amiable ran aground and was damaged beyond repair. Native pillagers swamped the abandoned ship, but la Salle was quick to take advantage. He stole their canoes, but lost several more men in an ensuing battle. What remained of the original band of adventurers set out once more on the Belle, now desperately searching for the Mississippi River.

Still convinced that the river was close by, la Salle set up Fort Saint Louis near present-day Victoria Texas with his remaining 36 colonists. From here, he would launch forays eastward attempting to locate the river he and Tonti had canoed down just a few years prior. By now, those few surviving colonists had survived incredible hardships: sickness, attacks, desertion. It was from this desperation that Pierre Duhaut conspired with a handful of men to kill La Salle while on their forth overland expedition in search of the Mississippi River on March 19, 1687.

Ironically, another member of the expedition killed Dehaut over a dispute about the allocation of supplies. The few remaining explorers, including one Henri Joutel, continued eastward, and finding the Mississippi River, they returned north to find Henri de Tonti. Keeping the true story to themselves, they told Tonti only that they had become separated from la Salle. Tonti, not knowing that he was, in fact, facing la Salle’s murderers, secured passage for them back to France. It was not until Joutel published his journals in 1713 that the truth of la Salle’s murder would be known.

La Salle’s Fort Saint Louis colony lasted only until 1688 when Native Americans killed the 20 remaining adults and took the children as captives. Tonti sent out search missions in 1689 when he learned of the settlers’ fate, but failed to find survivors. Tonti himself had undertaken an excursion down the Mississippi River into southern Louisiana in 1685 in search of his old friend, la Salle, hoping to meet him and his arriving colonists. Disappointed at finding no trace of la Salle, Tonti left a letter with the local Indians at the village of Bayagoulas along the Mississippi River near Lake Maurepas. Amazingly, this “speaking bark” was handed over to Bienville 14 years later when he began to explore the area. It was from the letter that Bienville gained confidence that his team had found the Mississippi River.

In 1995, La Salle’s ship Belle was found in Matagorda Bay and has since been the site of archaeological research. Most important to La Salle’s legacy though are the contributions he made to the increased knowledge of the Great Lakes region and the Mississippi Basin. His claiming of Louisiana for France has a significance that lasts to this day in terms of the physical layouts of the cities and the cultural practices of the people there.

Join Royal Tours

for one of our fascinating private walking tours of the French Quarter, and you'll see why people say being on tour with Royal Tours

is like having a new best friend in the French Quarter! Call us 504-507-8333 or email us

to book your private French Quarter tour.

N orma Wallace, a name that evokes intrigue and fascination, was a prominent figure in New Orleans during the early and mid-20th century. As a powerful and resourceful madam, she operated a network of brothels that thrived despite the constant threat of law enforcement. Beginning in 1920, she would operate brothels for the next 45 years, a span that has not been beaten in the history of New Orleans.