Robert de La Salle and the French Claim of Louisiana, Part 1

Royal Tours New Orleans • October 24, 2017

Robert de La Salle and the French Claim of Louisiana, Part 1

Rene-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle, first feasted his eyes on the Mississippi River in January, 1682. His companions were forty soldiers, three monks, and the Chevalier de Tonti. La Salle had received the education of a Jesuit and had been destined to the cloister and to become a tutor of children in the seminary of that order. But, he had a will, and a passion, and an intellect that would drive him to become an explorer.

Though born poor, he desired to be noble and rich; obscure, he desired to be famous. So, he obeyed the impulse of his ambition and crossed the Atlantic, landing in Canada in 1673. Once in the New World, La Salle’s mind seemed to expand, his conceptions became more vivid, and his eloquence became more persuasive.

Brought into contact with Count Frontenac, the governor of Canada, La Salle told him of his views and projects for the aggrandizement of France and suggested to him the grand plan of connecting the St. Lawrence with the Mississippi by an uninterrupted chain of forts. “From the information which I have been able to collect,” La Salle said to the Count, “I think I may affirm that the Mississippi draws its source somewhere in the vicinity of the Celestial Empire, and that France will be not only the mistress of all the territory between the St. Lawrence and the Mississippi, but will command the trade of China, flowing down the new and mighty channel which I shall open to the Gulf of Mexico.”

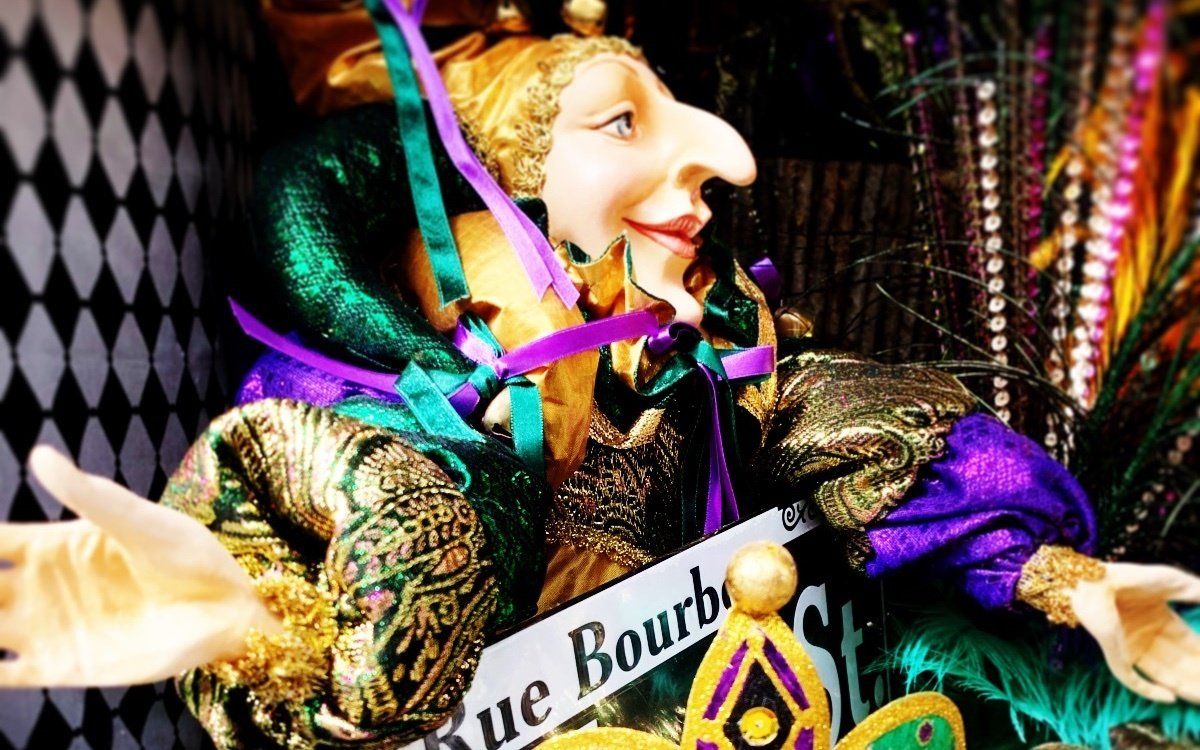

To learn more about the fascinating history of New Orleans and the French Quarter, join Royal Tours

for a private French Quarter History Tour. This is a great way to gain insider secrets on the French Quarter while on vacation in New Orleans.

Count Frontenac was mightily seduced by the grandness of La Salle’s plan, but he feared incurring such an expense and so referred La Salle to the court of France for approval. Returning to France with a letter of introduction from Count Frontenac, La Salle was introduced to Prince de Conti who was immediately fired by La Salle’s enthusiasm. Through Prince de Conti, La Salle obtained from King Louis XIV not only an immense concession of land but was provided all the powers and privileges needed to carry out his plans of discovery.

In 1678, La Salle re-crossed the Atlantic with his new partner, the Chevalier de Tonti, who, as an officer, had served with distinction in many a war, and who afterward became famous among the Indians for the iron hand which replaced his own which he had lost in battle. La Salle soon stood once again in Quebec and began the execution of his projects. But, over the next four years, La Salle and Tonti would face sunken ships, mutinous soldiers, burning forts, and Indian friends turned foe.

In February, 1682, La Salle and Tonti finally launched their canoes into the icy waters of the Mississippi. In addition to Tonti, la Salle’s party consisted of more than forty Europeans and Native Americans. While navigating the Mississippi, la Salle stopped to construct Fort Prudhomme which later became the site of Memphis, Tennessee.

With the assistance of Arkansas Indian guides, La Salle’s group finally reached the point at which the Mississippi River flowed into the Gulf of Mexico (near present-day Venice, Louisiana) where he buried an engraved plate and planted a post with the inscription “Louis the Great, King of France and of Navarre, Reigns Here, April 9, 1682.” The king would not learn of La Salle’s discovery until a year later. On April 10, without taking the opportunity to explore the Gulf Coast and the Mississippi’s intricate web of tributaries, La Salle began the return voyage up the river. Once back in Illinois, la Salle and Tonti built Fort Saint Louis at Starved Rock in Illinois. La Salle left Tonti in charge while he returned to France to plan his next exploration.

Royal Tours New Orleans

offers private walking tours of the French Quarter. There is no better introduction to the French Quarter than a private tour from Royal Tours. Joins us and you'll see why being on tour with Royal Tours

is like having a new best friend in the French Quarter. Call us at 504-507-8333 or email us

for details.

N orma Wallace, a name that evokes intrigue and fascination, was a prominent figure in New Orleans during the early and mid-20th century. As a powerful and resourceful madam, she operated a network of brothels that thrived despite the constant threat of law enforcement. Beginning in 1920, she would operate brothels for the next 45 years, a span that has not been beaten in the history of New Orleans.